The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye by Sonny Liew

I don’t seem to have the nostalgia bug that many comics readers have. I don’t feel the need to reread the Herb-Trimpe-drawn Hulks that were my first purchases from 25-cent bins. There are books that I can reread many times — Paul Chadwick’s “Concrete” and “Jar of Fools” by Jason Lutes come to mind — but those are rare. I like to move forward.

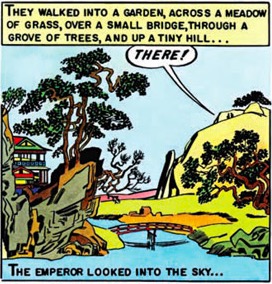

Art by Sonny Liew

“The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye” is a book from 2016 by Sonny Liew. The cartooning brings to mind a cliche of reviews: It is a bravura feat of artistry. In terms of the styles of art, the design of the various materials that the story presents through layout, and coloring and tones, Liew demonstrates such a facility with his goal of depicting the various layers and levels of a long-lived artist’s life that I had to study the book for several minutes to determine that it was the work of only one artist.

Art by Sonny Liew

The story, in the aspect of comics-making, may go too far in depicting the different styles of the titular artist. When I think of the people who made comics and art for more than 50 years such as Kirby, Davis, or Eisner, none of them changed their styles so drastically once they reached maturity. While I love 1940s Jack Kirby art, once he hit the 50s, his style had mostly coalesced and he only made incremental stylistic changes to his art, revising layout approaches and fine-tuning the mark making over time. Will Eisner’s brush seemed to loosen and gain emotion in the last 30 years of his life, but other than that, I don’t see a dramatic shift in style, he was already experimenting with his layouts in the 40s. Jack Davis got looser but was immediately identifiable to fans of his overwhelmingly detailed 50s EC work.

In service of making the book look like the work of another artist, one who had a long career with many various projects, Liew went a little too far in varying the styles. The transition from the rudimentary, early-career manga-style work to Kurtzmanesque 50s work, to Mort Drucker-style 60s to Walt Kelly to Frank Miller to Carl Barks storytelling designs seems an unlikely transition for a lifelong comics maker who is renowned. I can see the oil paintings as a reasonable change in style; the medium can change the message, of course.

Interestingly, this flaw actually highlights a great strength of the author. I hadn’t seen such adeptness in his comics work previously to suggest such an ability to ape styles and techniques from throughout comics history. The Tezuka-influenced early work of the fictional artist is obviously drawn by the same artist as the Pogo riff mid-book, or the 80s grim and gritty comics that appear later, but the change in styles is admirable. Even Mad Magazine would have different artists for most parodies, Wally Wood being a notable exception in the ability to ape fellow creators (“Never draw anything you can copy…”). Art seen in an early aughts Sonny Liew Marvel story intended to be in 60s style didn’t show a desire to copy the stylistic ephemera of Ditko or Kirby. It remained wholly identifiable as Liew.

Here I have to admit to being a poor reader for a major aspect of this book. I had honestly never thought twice about the history of Malaysia or Singapore. My entry into this story was comics, and being quite familiar with the history of them allowed me to not become overwhelmed by the density of the historical material. I fully admit that I finished the book with a nominal knowledge of the facts behind it, which is not a flaw of the author.

Art by Sonny Liew

Coming to the history and politics of Singapore so cold, I had a hard time evaluating whether the metaphors designed for the work of “Charlie Chan Hock Chye” were heavy-handed or adept. Liew is constantly providing context, but I am probably missing some subtleties that make these allegories more creative and engaging. For example, it was difficult to tell if the political message of the Harvey Kurtzman E.C. pastiche was broad and unsubtle because many of Kurtzman’s stories were the same, or if it had a subtext that I was missing as an ineffective reader. There is a Walt Kelly Pogo-style strip later that feels like it holds a little more nuance, but then a later story, with running commentary by “Sonny Liew” reads as though it is teenaged parody, akin to the worst of Mad Magazine.

I also wonder whether readers who don’t share my knowledge of comics so immediately recognize the forebears of the styles in the book, which gather the context of time and history they mean to entail. There are endnotes which define some of the comics creators whose styles are referenced, but others are left out. I took a Frank Miller Dark Knight reference late in the book to encompass meaning in both the context of the sociopolitical landscape in which it was created (80s leftist Western Culture feeling overwhelmed by Reagan and Thatcher and the Cold War) and the context of the comics and manga industry which had been referenced earlier in the book (American Pre- and Post Code comics, British and Japanese post-war, e.g.), reading it’s tone as both reflective of the time and the mood of the “author”. The endnotes don’t mention Miller at all.

Speaking of the mood of the title character, my favorite aspect of the book is the consistency of definition of his personality. I was completely engaged with the story of this man, and how he navigated his world, personal and political. He is so fully defined that late in the book, I found myself thinking of him as a real person. The conceit of this being a biography became realized and I was invested in his story to the point that I wondered what happened to him after the end.

This book is certainly the work of an artist who has matured in his storytelling to a point of being able to deliver an engaging, intelligent, cohesive narrative told across a man’s life and bring it all together through disparate styles into a compelling narrative of both man and country.